This story is published in partnership with The Houston Chronicle.

Some Texas lawmakers are calling for state regulators to better protect residents from the highly toxic gas hydrogen sulfide, which leaks from aging oil facilities near families and schools.

Two legislators said they are looking into filing legislation, another said she would call for hearings, and still others are reaching out to regulators to follow up on the problems identified in an investigation by The Examination and the Houston Chronicle.

The investigation found that oil companies are releasing hydrogen sulfide into residential neighborhoods with few or no repercussions. Known as H2S, the foul-smelling gas forms underground, comes to the surface with oil production, and can leak from storage tanks. High concentrations kill people quickly, and chronic low-level exposure has been linked to neurological and other health problems. The state has a limit for H2S in the air, but regulators broadly disregard it, downplaying the health threats, the investigation found.

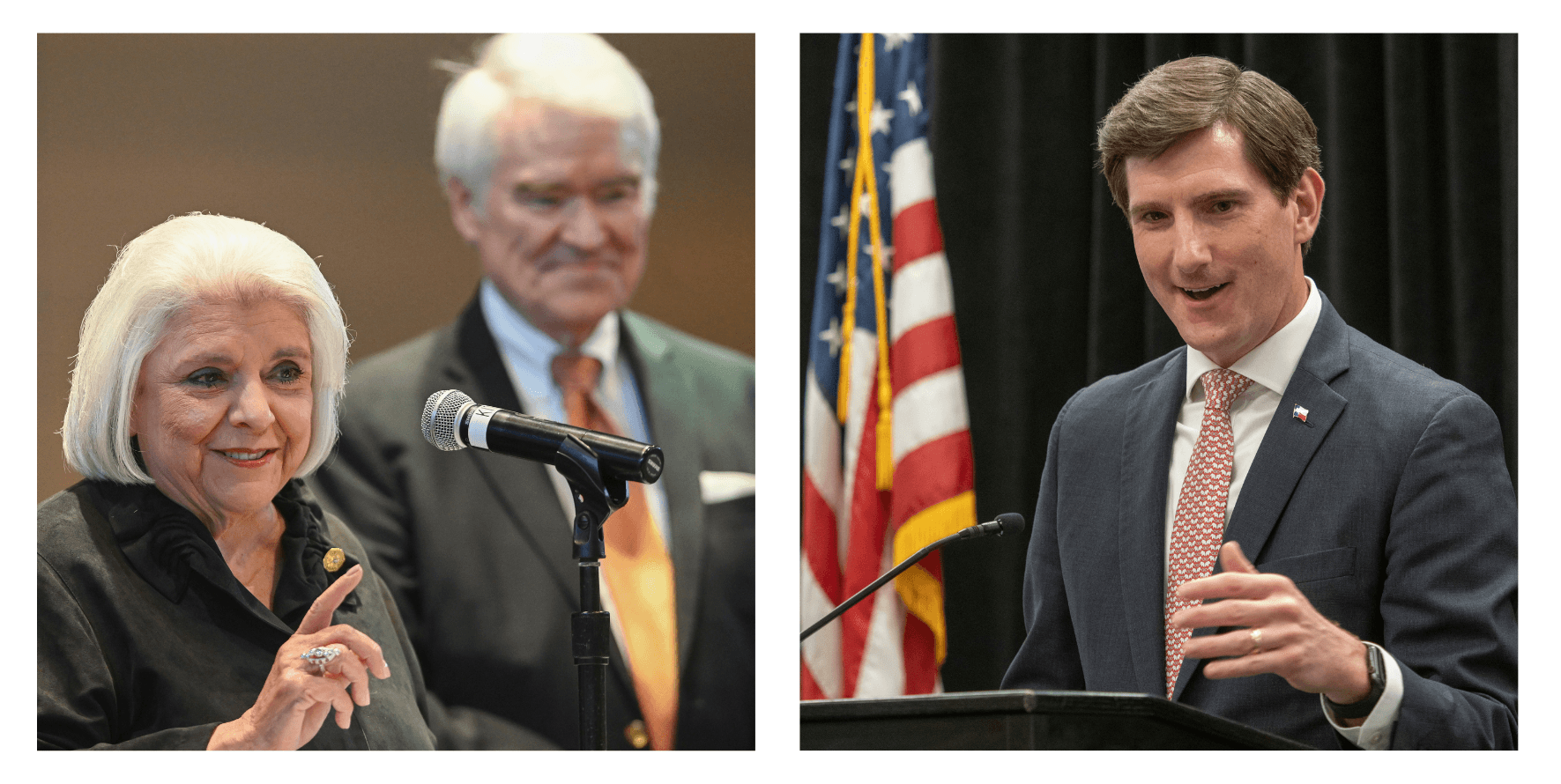

State Sen. Judith Zaffirini, a Laredo Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, said one of her priorities next session, starting in January, will be to make sure regulators are “funded adequately to monitor H2S levels and to deal appropriately with violators.”

The longest-serving state senator, who has passed more bills than any Texas legislator, Zaffirini said she’s looking into legislation to reduce H2S leaks, including requiring repeat offenders to upgrade their equipment and establishing a fund for smaller operators to do so. Legislation may also include prohibiting the venting of H2S near population centers and directing the Department of State Health Services to study the health risks of H2S exposure. Zaffirini is also considering requiring the Railroad Commission of Texas, which regulates the oil industry, to map and collect data on oil storage tanks, a common source of leaks.

“As a Senator whose district includes families living beside thousands of production wells, I prioritize efforts to ensure their safety and their protection from any possible hazardous concentrations of hydrogen sulfide,” Zaffirini said in an emailed statement.

Rep. Brooks Landgraf, Republican chair of the Environmental Regulation Committee, represents a West Texas district that includes Odessa, where investigators have found repeated H2S leaks near residents and elementary school students.

“As a born-and-raised Odessan who chooses to live with my family in this community, I take any reports of dangerous environmental conditions extremely seriously,” Landgraf said in an emailed statement.

Landgraf said he’s working closely with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which regulates air quality, and the Railroad Commission “to ensure that proper procedures are being followed.” He encouraged state agencies “to be transparent and accountable to the people of Texas.”

In response to Landraf’s inquiries, TCEQ sent him a statement that the investigation by The Examination and the Houston Chronicle “misconstrues” its response to H2S problems. It said the agency takes complaints seriously, does “extensive outreach” to the oil and gas industry, and conducts air monitoring surveys and follow-up investigations. It added that the agency is deploying a new mobile monitoring vehicle in the Permian Basin.

“When violations are identified,” the statement said, “we use our enforcement process to ensure that corrective and preventative actions are taken, and penalties are assessed to deter future noncompliance.”

The agency’s statement didn’t address the investigation’s finding that violators are seldom penalized and problems continue. When the agency did issue enforcement orders to a repeat violator in Odessa, the fines were for several thousand dollars and still the company hadn’t complied years later, records showed.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Global health reporting, straight to your inbox

TCEQ provided Landgraf’s office with a tally of complaints it received that specifically mentioned H2S, showing 89 since 2018. The agency didn’t count complaints that mentioned the smell of rotten eggs or other clear signs of H2S. The agency’s complaint data often includes only vague summaries, such as “oil and gas odors” for H2S-related problems.

The toxic gas has been leaking for years from an oil facility in Odessa, across the street from the home of Vanessa Hinojos and her family. But of the 10 related complaints to TCEQ since 2018, only two include the name of the gas in TCEQ’s data. Hinojos’ February complaint about H2S, for example, is described as, “Complainant alleges odors coming from a tank battery causing nausea.”

After investigators repeatedly found H2S leaking from the facility this year, TCEQ issued a notice of enforcement in May to Alan Means, owner of the operator of record, Cambrian Management. It said the company repeatedly failed to keep pollution control equipment in good working order. That could lead to fines but is pending, as is another similar enforcement action from 2023.

TCEQ concluded its investigation after an inspector’s visit in early May did not find any problems. A hydrogen sulfide monitor placed by a reporter in the Hinojos yard found H2S levels above the state limit around the same time.

Means has previously said, “We treated everybody as good as we could over there” and that he transferred day-to-day management of the facility to Octane Energy.

Lori Blong, mayor of the nearby city of Midland and co-founder of Octane Energy with her husband Jared, did not respond to requests for comment. Jared Blong said by email that recent site visits by TCEQ have “verified the production facility is properly maintained and does not pose a danger to nearby residents.” He said the company requested a voluntary TCEQ inspection and that “the safety and well-being of our team, neighbors, and community and the prudent stewardship of the environment are top priorities.”

Meanwhile, Hinojos said the problem continues. “What are they really going to do,” she asks of regulators. “Where’s the action?”

Eye on H2S hotspots

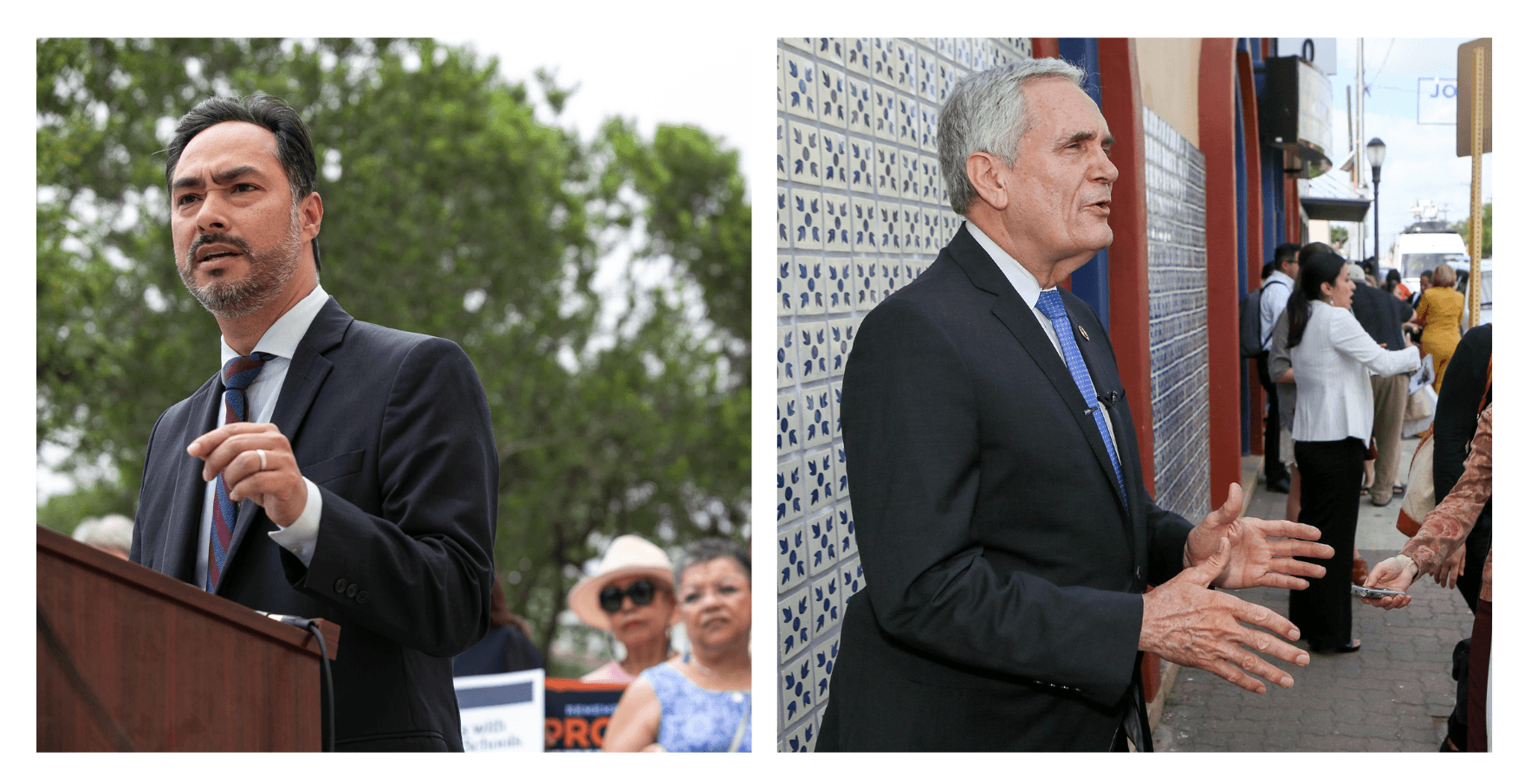

Rep. Ron Reynolds, a Missouri City Democrat, said he will file a bill next session requiring TCEQ and the Railroad Commission to do a “targeted study to jointly look at toxic hotspots.” Saying the agencies “need to step up and do their job,” Reynolds called for more air monitoring stations, more cooperation between agencies and more funding for enforcement.

The Houston Chronicle and The Examination mapped for the first time more than 54,000 wells in Texas that, according to state records, are part of oil and gas operations that have tested for high concentrations of H2S. But there were limitations because of the way the Railroad Commission collects data. Reynolds said the commission should make more information available to “help people living near wells to make their own decisions about what they want to be exposed to.”

“I have grave concerns over the oil companies’ blatant disregard and poisoning our communities with toxic hydrogen sulfide gas,” said Reynolds, who sits on the House Environmental Regulation Committee, in an email statement.

Rep. Penny Morales Shaw, a Houston Democrat on the Environmental Regulation Committee, said TCEQ “should not be pardoning repeat environmental offenders at the expense of public health.”

“In the coming days, we will work with TCEQ to address this,” she said in a text message.

TCEQ spokesperson Ryan Vise told The Examination the agency is constantly reviewing its processes. “The agency pursues swift, fair, sensible, and responsive enforcement, used within an overall strategy for achieving timely compliance,” he said.

The agency declined an interview request with its governor-appointed chairman, Jon Niermann, and its executive director, Kelly Keel.

The news outlets found that inspectors return to the same leaking oil tanks again and again as problems persist for years. The Railroad Commission’s former statewide hydrogen sulfide coordinator has called for stronger regulations.

Asked whether the commission plans to make any changes, spokesperson Patty Ramon reiterated that it closely monitors facilities, especially near schools and homes, and when inspectors find problems, “they work to ensure violations are resolved immediately.”

“The state’s H2S rules are in place to protect Texans and the environment, and our inspection and enforcement of the rules are extensive,” Ramon said by email.

Rep. Shawn Thierry, a Houston Democrat who recently lost a primary runoff, said she is going to request hearings on the issue. A spokesperson said she plans to ask the chairs of the Environmental Regulation and Energy Resources committees to hold hearings, since they oversee TCEQ and the Railroad Commission, respectively.

“These legislative inquiries will also enhance transparency and oversight ensuring the public health and well-being of all Texans,” said Thierry, a member of the Energy Resources Committee, in an emailed statement.

Republican Rep. Craig Goldman, chair of the Energy Resources Committee, is currently running for Congress and did not respond to inquiries.

A couple of members of Congress from Texas also raised concerns about hydrogen sulfide.

“The health of too many Texans continues to be endangered by multiple failures to protect them from this poison,” said U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, a Democrat who represents Austin, in an emailed statement. Doggett said the news investigation brought the problem to his attention and he looks forward to learning more to determine next steps.

U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro, a Democrat who represents San Antonio, said “the federal government and our state government in Texas both need to do a better job of regulating hydrogen sulfide exposure.” U.S. Rep. August Pfluger, a Republican whose district includes Odessa, did not respond to a request for comment.

There are no federal air quality standards for H2S. Under pressure from the industry, the gas was removed from the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of “hazardous air pollutants” decades ago, leaving regulation to the states.

Legislation to add H2S to the EPA list, which would lead to pollution controls, has been introduced repeatedly by U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke, a New York Democrat, without success.

The Sierra Club and other environmental groups petitioned the EPA in 1999 and 2009 to put H2S on the list, and threatened to sue in 2011. An EPA spokesperson said the Sierra Club didn’t provide additional information, so the agency didn’t take action. Neil Carman, of the Sierra Club’s Lone Star chapter, helped lead that effort and said the EPA should have regulated H2S anyway. But because of political and industry opposition, he doesn’t expect the situation to change.

“I wish I could be optimistic,” Carman said, “but my crystal ball is showing me a pretty polluted future for Texas.”