This investigation is part of Nicotine Networks, an ongoing investigation by The Examination and Latin American news outlets. The Examination co-reported this story with Salud con lupa in Perú and LaBot in Chile. It is co-published in partnership with The BMJ in the UK and Spain's El Pais America.

SANTIAGO, Chile — Verónica García was 13 when she sneaked her first cigarette from a pack belonging to her dad. Her first puffs didn’t go well. “For a little girl who’s never smoked, those cigarettes are strong,” she said.

Soon after, friends gave the Chilean teenager a different type of cigarette. It was a Lucky Strike Double Click Crisp and had two flavor capsules lodged in the filter. When she crushed the capsules, the smoke she inhaled tasted like lemon and mint. By age 14, she was buying her own packs of flavored cigarettes.

Five years later, García still smokes.

Featuring splashy packaging, breezy names and kid-friendly flavors like blueberry, apple and menthol, these newer varieties — known as “click cigarettes” — are soaring in popularity across Latin America, where they’re star performers for tobacco giants British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International.

While much of the world wrestles with regulations around vapes and their many flavors, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco have been pumping flavors into conventional cigarettes and fighting efforts to ban the products in the region, according to a joint investigation by The Examination, Perú’s Salud con lupa and Chile’s LaBot news outlets.

Both firms have released dozens of new flavor capsule brands across Latin America in recent years — despite promises to phase out cigarettes in favor of newer nicotine products and vows not to market tobacco in ways that appeal to children.

The two companies dominate sales in Latin America — promoting their brands to young people through tactics such as showcasing cigarettes at music festivals and launch parties at dance clubs.

In Chile, brands like berry-flavored Lucky Strike Fresh Wild now account for 42% of the cigarettes sold in the country, up from less than 2% in 2009, according to Euromonitor International. In Perú, flavored cigarettes make up more than half of sales. In Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala and México, more than one in five cigarettes sold contain flavor capsules.

“It's like making a cocktail instead of drinking … I don’t know, plain hard liquor,” said Alenlafken Escanilla, a Chilean 18-year-old who has been smoking socially for three years.

The products are banned or restricted by the European Union’s 27 member nations as well as Canada and at least 20 other countries. In the U.S, capsule brands like Camel Crush and Marlboro NXT are allowed only in menthol varieties and account for just a sliver of the market.

The growth in popularity of capsule cigarettes — also sold in Russia and parts of Asia and Africa — is drawing the attention of researchers, policymakers and doctors. Tobacco-related diseases are estimated to cost health ministries in Latin America close to $34 billion a year and contribute to more than a quarter million deaths in the region annually, according to calculations by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Cigarettes containing flavor capsules are “a huge, global public health threat,” said Crawford Moodie, a researcher with the University of Stirling in Scotland, who has studied flavored cigarettes for years. Children and young people view them as cool, high-tech and novel, Moodie said. “It makes smoking fun.”

Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco both say their products are not intended for children.

Philip Morris International responded to a request for an interview and detailed questions with a statement that did not specifically address flavored cigarettes and instead highlighted its investments in alternative nicotine products. “We comply with all local laws, as well as our own strict marketing code that often goes far beyond what is legally required,” said Corey Henry, a spokesman for the Stamford, Conn.-based company, in an email.

“We do not encourage people to start smoking, nor do we discourage cessation,” says a summary of the company’s marketing code of conduct posted to Philip Morris International’s website. “We do not want minors to use any PMI product and we do not market to minors.”

The company’s site also says that it assesses flavors before putting them on the market to “minimize the risk of adverse consequences, including appealing to youth and other unintended audiences.”

Similarly, London-based British American Tobacco, whose brands include Lucky Strike, Pall Mall and Kent, says on a web page labeled “Ethics and Integrity” that the company’s “marketing is aimed only at adult consumers and is not designed to engage or appeal to children.”

“We are clear that our tobacco and nicotine products are for adults only and should never be used by those who are underage,” a spokesman for British American Tobacco said in an emailed statement. “We abide by strict marketing principles, in addition to requirements under local law to prevent marketing and sales to underage.”

‘A better tomorrow’ includes fruit flavors

In 2016, Marlboro-maker Philip Morris International announced it had a new purpose: to deliver a smoke-free future.

The company had recently launched its iQOS heated tobacco device, which it promoted as a potentially lower risk alternative to cigarettes. Philip Morris International’s new goal: “ultimately replace combustible products to the benefit of adult smokers, society, and our company.”

Yet over the next eight years, Philip Morris International introduced at least 30 new flavor capsule cigarette brands into Latin American markets, including watermelon-flavored Marlboro Summer Zest and cherry- and menthol-flavored Marlboro Blossom Fusion, a review of government records, scientific research and other reporting by The Examination found.

Just last year, company executive Werner Barth touted Marlboro’s top position in capsule cigarettes in a meeting with investors, highlighting the company’s success in markets from México to Algeria. The products are one of the few growing areas of the global cigarette market, he noted.

In 2020 Philip Morris International’s main rival, British American Tobacco, announced that it, too, would move away from the cigarette business and concentrate instead on switching smokers to newer products it described as posing a reduced risk, such as its Vuse vaping device. The company went so far as to trademark the name for its vision: “A Better Tomorrow.”

But then, just like its rival, the company continued to roll out new lines of cigarettes featuring fruity flavors. Across the region, British American Tobacco released at least 27 new flavor capsule brands after “A Better Tomorrow” was announced, The Examination found.

This included cigarettes with names like Kent Neo Tropic and Pall Mall Sunrise Mix. Among the flavors British American Tobacco embedded in its cigarettes: berries, melon and even a flavor that retailers and others said resembled the energy drink Red Bull. Its name: Lucky Strike Charged.

Joanna Cohen, director of the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said it’s what the tobacco companies do rather than what they say in public that matters.

“They can talk out of both sides of their mouth at the same time,” Cohen said. “You can't take what they're saying at face value.”

‘I got hooked immediately’

Menthols were the first flavored cigarettes to gain mass appeal in the U.S. in the 1950s. Made by adding the minty flavoring to the tobacco or rolling paper, they were cherished by users for numbing the throat and masking the harsh taste of burning tobacco.

In the late 1970s, Lorillard Tobacco Co., later absorbed by British American Tobacco, researched marshmallow, cherry, creme de menthe and tutti-frutti flavored cigarettes, concluding some flavors would appeal to consumers who were “very young,” “teenagers” and “beginner cigarette smokers,” records show.

It’s almost their way of sneaking Joe Camel back on the market.

Dale Mantey, UTHealth Houston School of Public Health

Capsule cigarettes hit the market in 2007. That year, British American Tobacco released the first capsule cigarette in Japan — a Kool Boost featuring menthol flavoring. Soon after, Camel Crush menthol capsules debuted in the U.S., made by Reynolds American — then part owned by British American Tobacco. And by 2010, Philip Morris International, too, was in the capsule game.

Since then, the number of flavors has exploded. Lemonade. Lollipop. Strawberry. That’s how some of the more than three dozen Chileans aged 14 to 27 recently interviewed by The Examination described the taste of click cigarettes.

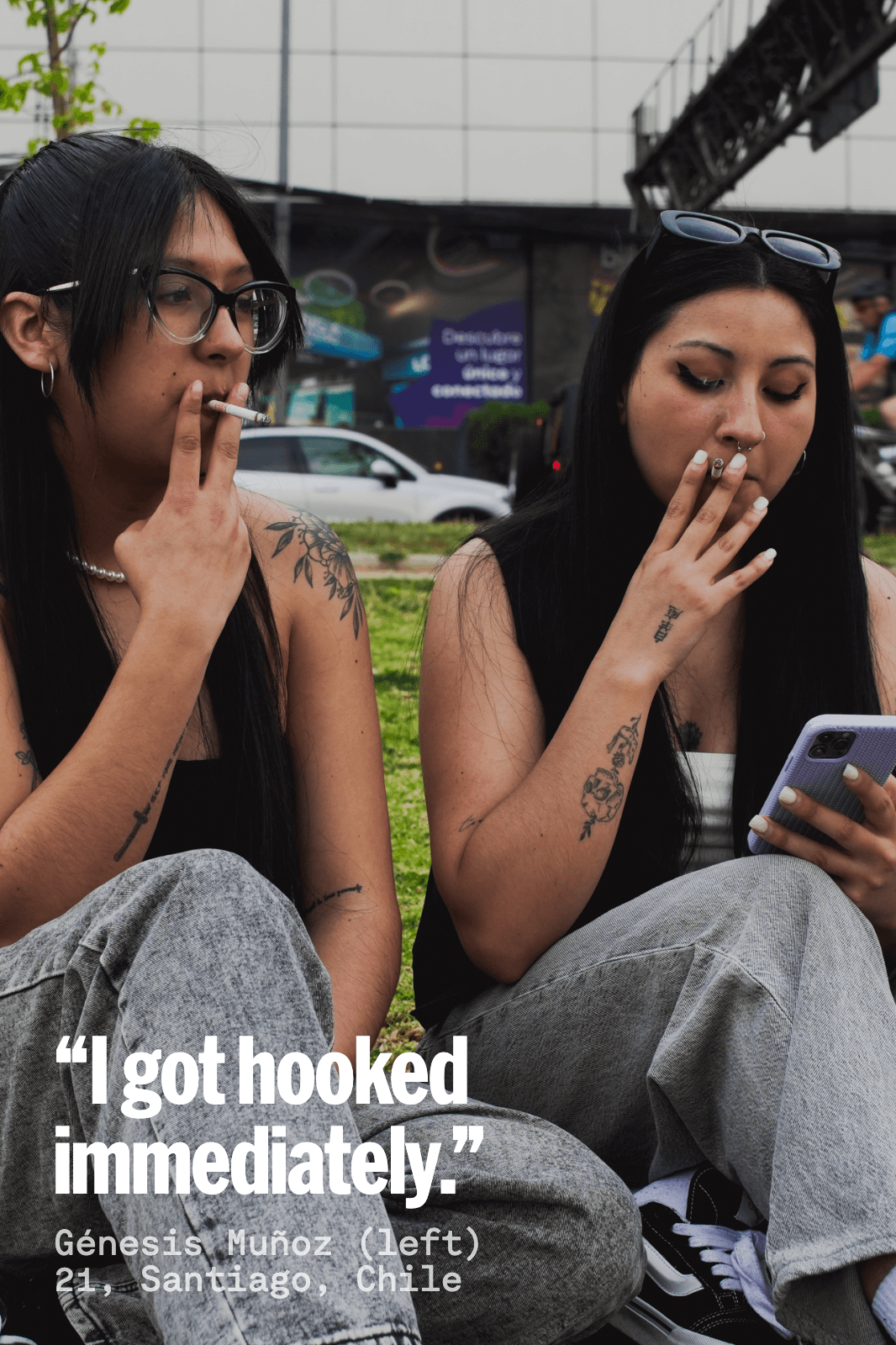

“I got hooked immediately,” said Génesis Muñoz, a 21-year-old who started smoking British American Tobacco’s berry-flavored Lucky Strikes when she was 17. They tasted like fruity gum. She then moved on to an orange-flavored variety of the same brand.

Muñoz and her friend Fernanda Echeverría sat on the grass in a park in Santiago, drinking beer and smoking Philip Morris International’s watermelon-flavored Marlboro capsule cigarettes. Both said they hate plain cigarettes.

“They were bad,” said Echeverría, who started smoking at age 15. “They gave me migraines, headaches, made me feel dizzy, nauseous.”

Yet the ones with capsules “were like chewing gum,” she said.

Iñaki Ariztía, 18, said he first smoked at 12. It was a click cigarette, which he now describes as “sweeter” and “more refreshing” than unflavored tobacco.

“It makes it easier to get used to smoking,” he said, standing on a tree-lined street in Santiago outside of Alianza Francesa, where he is a high school student. Ariztía has since switched to unflavored tobacco and smokes five or six hand-rolled cigarettes a day.

Were it not for capsules, he likely wouldn’t have begun smoking so young, he said. “Or maybe, I would have tried it, but I wouldn’t have kept smoking.”

The appeal of flavored cigarettes to children stretches well beyond Chile. In México, one recent study estimated that half of smokers aged 10 to 19 used capsule cigarettes. In Argentina, another found that about 75% of teen smokers in Buenos Aires reported using flavored cigarettes.

Philip Morris International has acknowledged that sweet and fruity flavors are a big reason why teenagers start using another nicotine product — vapes. In 2023, the company supported flavor restrictions for vapes in the UK “to limit undue youth appeal.”

The candy-like flavors and flashy packaging are just a continuation of the tobacco industry’s long-running practice of targeting teenagers, says Dale Mantey, a professor at UTHealth Houston School of Public Health in Texas. “Fruity flavors really appeal to youth,” he says. “Not just the flavors, but the marketing, the bright colors…it’s almost their way of sneaking Joe Camel back on the market.”

Selling “Cool Kids”

Effective marketing to young people explains part of the industry’s success. A 2016 video ad for British American Tobacco’s berry-flavored Lucky Strike Double Click Wild in Perú features young models running in bathing suits to the tune “Cool Kids” by the pop band Echosmith. The group, which then featured an 18-year-old singer and a 16-year-old drummer, garnered nominations for the 2015 Teen Choice Awards and that year’s Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards.

That same year, at an outdoor launch party for Lucky Strike Indigo capsule cigarettes at Santiago’s University Andrés Bello, attendees smoked, drank and donned virtual reality headsets, according to photos of the event posted to social media. In 2017, a lively in-house video celebrating Lucky Strike Indigo’s success in Perú and Chile featured montages of young people dancing and partying while teen heartthrob Shawn Mendes’ “Stitches” pulsed in the background.

Music has been a pillar of Philip Morris International’s marketing efforts as well. Just this year in Perú, the company promoted one of its capsule brands by raffling tickets to DGTL Lima, an electronic music festival and dance party.

And in Colombia, the company has sponsored the Estéreo Picnic music festival for the past several years. One of the largest musical events in Latin America, the four-day concert features pop stars like Billie Eilish, Olivia Rodrigo and Lil Nas X. At the festivals, Marlboro capsule cigarettes were marketed at neon-lit kiosks and by backpack-clad models meandering through the crowds of young people near the entrance, according to a report from the watchdog group Corporate Accountability.

“It’s evidence that the smoke-free world strategy of Philip Morris is simply a facade,” said Jaime Arcila, co-author of the report.

Last year, the market share for capsule cigarettes in Colombia rose to 33% — more than triple what it had been in 2017, according to Euromonitor.

Fighting flavor bans

Public health experts say banning flavors in cigarettes can significantly reduce the number of minors who smoke.

In the U.S., for example, one study estimated that a 2009 ban on non-menthol flavorings reduced teenage cigarette use by 17%. Another put the figure at 43%.

Guidelines to an international treaty on tobacco control recommend that the more than 180 member countries ban or restrict cigarette flavorings.

It’s evidence that the smoke-free world strategy of Philip Morris is simply a facade.

Jaime Arcila, Corporate Accountability

Yet, efforts to outlaw flavors have failed across Latin America. In México, the region’s No. 3 market, a bill that would outlaw flavored tobacco died in the senate earlier this year. In Perú, a tobacco control bill included a proposed ban on flavored nicotine products, but the provision was dropped shortly before Congress passed the bill last month.

In Brazil, trade groups whose members include British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International first challenged a ban on tobacco flavorings in court in 2012, prompting a delay in implementation that continues today. Both companies have been releasing new capsule brands in the interim.

Perhaps nowhere has the industry’s might been so starkly on display as in Chile. While cigarette sales have been gradually declining for more than a decade, the country still has the highest rate of tobacco use in the Western Hemisphere. Nearly 30% of Chileans used tobacco in 2020, according to the World Health Organization. And the average age that teens start is 13.

Public health officials tried to block flavors before they became widely available, launching an opening salvo in 2011, when capsule brands were less than 4% of the market.

That year, the health ministry sought to ban flavorings under a law that gave it the authority to outlaw ingredients that increased harm to smokers. But the ban was quickly blocked by another administrative office — that of the comptroller general — that can reject regulations on legal and constitutional grounds. The comptroller said authorities hadn’t proven that the flavor additives harmed smokers.

The health ministry tried a new ban — limited to menthol — again in 2013, after Chile’s Congress gave it the power to also ban additives that make cigarettes more addictive. Again it was rejected by the comptroller general’s office. When the health ministry asked the comptroller’s office to reconsider its decision, British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International filed documents opposing the petition. Once again, the health ministry lost.

What was not widely known was that Chile’s comptroller general at the time, Ramiro Mendoza Zúñiga, had represented British American Tobacco as a lawyer on local regulatory matters until the day before he took office in 2007, according to documents obtained by The Examination and LaBot.

Mendoza himself had signed the first decision blocking a flavor ban in 2011, and that early ruling was cited as precedent by a deputy, who ruled against the menthol ban in 2013.

“I would have expected that someone ethical would recuse himself,” said Guillermo Paraje, a professor and health economics researcher with the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez in Chile.

Short of that, someone should have stepped forward, Paraje said. “If he doesn’t recuse himself, the institutions are there to tell him, ‘Can you opine on this, having been a lawyer for one of the parties?’”

Mendoza declined to explain his actions to The Examination and LaBot, saying he hasn’t been comptroller general for almost a decade.

Over the next several years, lawmakers continued attempts to ban flavors as capsule brands exploded in popularity —increasing their market share to 30% by 2015.

Amid the efforts, British American Tobacco –by far the biggest player in Chile– threatened to close operations in tobacco-growing regions and shutter its cigarette manufacturing plant if a bill that included a flavor ban became law.

Thousands of Chileans, including a “significant” number of growers and workers would be affected, the company argued. Moreover, smuggling would increase and tax authorities would lose up to $400 million a year as a result of the ban and another of the bill’s measures, the company said in a news release.

Tobacco workers, too, protested the ban and targeted individual senators who supported the bill, including former Sen. Guido Girardi, an outspoken opponent of British American Tobacco who called cigarette flavorings “criminal.” One banner, hung along a main thoroughfare, read “Giarardi doesn’t give a damn about our source of work.” Another read “Tobacco Law = 5,000 unemployed.”

British American Tobacco’s campaign against the bill was “full of lies and threats,” Girardi said.

When the proposed ban regained momentum in 2021, British American Tobacco — then publicly committed to “A Better Tomorrow,” once more opposed it. The bill has been stalled since.

Celso Muñiz, manager of the Chilean government’s Office for the Prevention of Tobacco Consumption, says industry pressure on the issue has been unrelenting.

“It's constant, whenever there’s progress in the legislative processes,” he said.

The industry’s success in staving off bans in Latin America has meant it’s kept customers like 20-year-old Martín Retamales, who started smoking click cigarettes at 17 to assuage his anxiety. He says plain cigarettes taste horrible, and he doesn’t smoke them even at parties when they’re the only ones available. Retamales said a ban on flavored cigarettes in Chile would surely impact his life.

“I’d quit smoking if they did it,” he said while taking a break in the courtyard of the University of Chile School of Law. “It would work with me at least.”

Jason Martínez of Salud con lupa and Fernanda Aguirre, Matthew Chapman and Ashley Okwuosa of The Examination contributed reporting.